David X Young

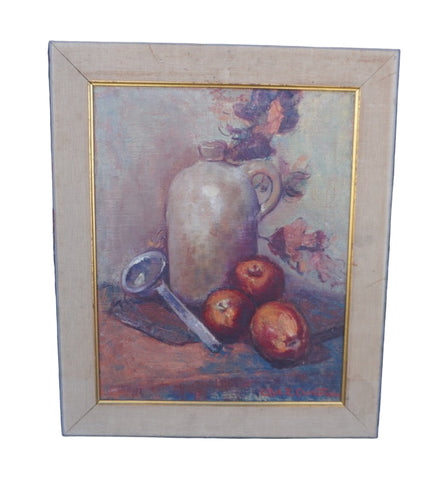

David X Young - Abstract Expressionist Oil on Canvas P3200

Regular price

$2,000.00

Measures 32" x 52". Jazzy, alive, deeply New York. Read the obituary below, it's a hell of a story.

The following obituary is from the New York Times, June 3, 2001

David Young Dies at 71; Painter and Friend to Jazz Artists by Douglas Martin

David X. Young, a painter whose rodent-infested, illegally rented loft became a citadel of Jazz improvisation and experimentation in the 1950s and 60s, died on May 22 in Manhattan. He was 71. The cause was a heart attack, said his daughter Eliza Alys Young.

The loft, in an industrial building at 821 Avenue of the Americas, near 28th Street, became a gathering place for the greats of Jazz, including Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie, as well as for utter unknowns who simply yearned to play. Known simply as the "the Sixth Avenue loft," it was one of maybe a half-dozen planes where musicians gathered at a time when various strains of jazz mainstream, bebop and cool, among others were percolating. Situated in the heart of the flower district, it was the epicenter of what became known as loft jazz.

"By most accounts, it drew the biggest names, showcased the latest talents and lasted the longest," said an article in the fall 1999 issue of Double Take magazine. "Guys played with people theyd never seen before," Bob Brookmeyer, a trombone player, said in the article. "Whites, blacks, old guys, young guys. Nobody cared about that stuff. We were all outlaws. Our profession wasnt considered respectable. There was a sense we were all in it together."

There was no lock on the lofts front door, and it was considered bad form to arrive before 11 p.m. There always seemed to be many pretty young women present, and ample bourbon and marijuana. It was a spot where Salvador Dali, Norman Mailer or Willem de Kooning might show up, entourage in tow. "The locus of mad freedoms, "Mr. Young once called the scene that his rent bargain made possible.

"It was my great pride and privilege to have initiated and hosted the spirit of that loft, to have lived within its joyous dark atmosphere and shared the antic energies of my very talented friends for more that a decade," he wrote. Mr. Young, of Jacksonville, Florida, who is his only survivor, said that the release of the CDs and the book, which included Mr. Young's Abstract Expressionist paintings inspired by the jazz scene, had revived his interest in art and life. National television featured reports on his loft, as did scores of newspapers. As a result, after many years of painting in solitude and ignoring commercial matters, he began putting images of his paintings on the Internet, most with $7,500 price tags. He sold them on his Web site, www.bluuchip.com.

He had always felt unappreciated, Ms. Young said, and was quick to express his resentment about it. "He saw himself as Picasso and expected everybody else to see that, " she said. "If they didn't, he didn't want anything to do with them."

David Benton Young was born in Boston on February 15, 1930. Ms. Young said he began using the middle initial X to give himself a sense of mystery. His father, Nelson, was a trumpet player who occasionally played with the jazz great Bix Beiderbecke. The elder Mr. Young suffered from depression, and committed suicide days after his son was born, Ms. Young said. Mr. Young was reared on Cape Cod by his grandparents, who he thought were his parents. He believed that his free-spirited mother, Kate Merrick, who wrote pulp novels, was his older sister. His ambition was to play jazz, but his grandparents, thinking of his father, forbade it.

He attended the Massachusetts School of Art in Boston. In 1951, when he was a sophomore, he exhibited his works at the Mortimer Levitt Gallery in Manhattan. After graduating a year later, he threw his diploma in the Charles River and headed for New York, where he became friends with Franz Kline and de Kooning and other Abstract Expressionists who congregated at the Cedar Bar in Greenwich Village. He needed a place to live that would give him enough space to paint the giant canvases others in the so-called New York School were doing.

While he was looking for a single-floor studio, the landlord at 821 Avenue of the Americas offered him the third, fourth and fifth floors for a total of $120 a month. "The place was desolate, really awful," he said in the article in Double Take. "The buildings on both sides were vacant. There were mice, rats and cockroaches all over. You had to keep cats around to fend them off. Conditions were beyond miserable. No plumbing, no heat, no toilet, no electricity, no nothing."

With $300 and some instruction from his grandfather, he made the place livable. Because occupying and industrial building was illegal, he bribed a building inspector with $75 each Christmas, he said, and kept big plywood boxes over the beds to hide them.

He began making money by painting covers for jazz albums and also spent more and more time in jazz clubs. "If hed spent as much time with the painters at the Cedar Bar as he did hanging around with us jazz guys, he might have become recognized as one of the great painters," said Teddy Charles, the vibraphonist.

Some of Mr. Youngs friends were having trouble finding adequate practice space, and he thought of his loft. "I checked around and found a good piano for $50, delivered.," he said. He had it hoisted up the outside of the building, and was ready to go. A couple of months later, the jazz composers Dick Cary and Hall Overton each sublet a floor from Mr. Young. Mr. Cary took a grand piano to his space, and Mr. Overton took two uprights. There were now four good pianos in the building.

Mr. Overton and Mr. Monk, both chain smokers, met frequently in the loft to prepare for elaborate concerts at Town Hall in 1959, Lincoln Center in 1963 and Carnegie Hall in 1964. "Theyd have the whole place filled with smoke," Mr. Young said in Double take. "They would sit at the two pianos for hours, working on their charts, smoking the whole time."

Davis, Mingus and Mr. Charles used the loft to home the sound heard on the record "Blue Moods." Regular jam sessions were on Monday nights. Mingus was in the loft on the night in 1955 when the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter called to tell him that Charlie Parker had just died in her living room.

In 1957, Mr. Overton rented some of his space to the photographer W. Eugene Smith, who shot 20,000 pictures of the sessions there. He and Mr. Young had planned to write a book on the loft scene, but Smith died in 1978.

Mr. Young, who also made several documentaries and science-fiction film, was finally evicted from his illegal space in 1964. He moved to a loft on Canal Street, where he survived by painting watercolors and occasional albums covers. He had been thinking recently about moving to Europe. "He got what he needed from New York," Ms. Young said.

David Young Dies at 71; Painter and Friend to Jazz Artists by Douglas Martin

David X. Young, a painter whose rodent-infested, illegally rented loft became a citadel of Jazz improvisation and experimentation in the 1950s and 60s, died on May 22 in Manhattan. He was 71. The cause was a heart attack, said his daughter Eliza Alys Young.

The loft, in an industrial building at 821 Avenue of the Americas, near 28th Street, became a gathering place for the greats of Jazz, including Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie, as well as for utter unknowns who simply yearned to play. Known simply as the "the Sixth Avenue loft," it was one of maybe a half-dozen planes where musicians gathered at a time when various strains of jazz mainstream, bebop and cool, among others were percolating. Situated in the heart of the flower district, it was the epicenter of what became known as loft jazz.

"By most accounts, it drew the biggest names, showcased the latest talents and lasted the longest," said an article in the fall 1999 issue of Double Take magazine. "Guys played with people theyd never seen before," Bob Brookmeyer, a trombone player, said in the article. "Whites, blacks, old guys, young guys. Nobody cared about that stuff. We were all outlaws. Our profession wasnt considered respectable. There was a sense we were all in it together."

There was no lock on the lofts front door, and it was considered bad form to arrive before 11 p.m. There always seemed to be many pretty young women present, and ample bourbon and marijuana. It was a spot where Salvador Dali, Norman Mailer or Willem de Kooning might show up, entourage in tow. "The locus of mad freedoms, "Mr. Young once called the scene that his rent bargain made possible.

"It was my great pride and privilege to have initiated and hosted the spirit of that loft, to have lived within its joyous dark atmosphere and shared the antic energies of my very talented friends for more that a decade," he wrote. Mr. Young, of Jacksonville, Florida, who is his only survivor, said that the release of the CDs and the book, which included Mr. Young's Abstract Expressionist paintings inspired by the jazz scene, had revived his interest in art and life. National television featured reports on his loft, as did scores of newspapers. As a result, after many years of painting in solitude and ignoring commercial matters, he began putting images of his paintings on the Internet, most with $7,500 price tags. He sold them on his Web site, www.bluuchip.com.

He had always felt unappreciated, Ms. Young said, and was quick to express his resentment about it. "He saw himself as Picasso and expected everybody else to see that, " she said. "If they didn't, he didn't want anything to do with them."

David Benton Young was born in Boston on February 15, 1930. Ms. Young said he began using the middle initial X to give himself a sense of mystery. His father, Nelson, was a trumpet player who occasionally played with the jazz great Bix Beiderbecke. The elder Mr. Young suffered from depression, and committed suicide days after his son was born, Ms. Young said. Mr. Young was reared on Cape Cod by his grandparents, who he thought were his parents. He believed that his free-spirited mother, Kate Merrick, who wrote pulp novels, was his older sister. His ambition was to play jazz, but his grandparents, thinking of his father, forbade it.

He attended the Massachusetts School of Art in Boston. In 1951, when he was a sophomore, he exhibited his works at the Mortimer Levitt Gallery in Manhattan. After graduating a year later, he threw his diploma in the Charles River and headed for New York, where he became friends with Franz Kline and de Kooning and other Abstract Expressionists who congregated at the Cedar Bar in Greenwich Village. He needed a place to live that would give him enough space to paint the giant canvases others in the so-called New York School were doing.

While he was looking for a single-floor studio, the landlord at 821 Avenue of the Americas offered him the third, fourth and fifth floors for a total of $120 a month. "The place was desolate, really awful," he said in the article in Double Take. "The buildings on both sides were vacant. There were mice, rats and cockroaches all over. You had to keep cats around to fend them off. Conditions were beyond miserable. No plumbing, no heat, no toilet, no electricity, no nothing."

With $300 and some instruction from his grandfather, he made the place livable. Because occupying and industrial building was illegal, he bribed a building inspector with $75 each Christmas, he said, and kept big plywood boxes over the beds to hide them.

He began making money by painting covers for jazz albums and also spent more and more time in jazz clubs. "If hed spent as much time with the painters at the Cedar Bar as he did hanging around with us jazz guys, he might have become recognized as one of the great painters," said Teddy Charles, the vibraphonist.

Some of Mr. Youngs friends were having trouble finding adequate practice space, and he thought of his loft. "I checked around and found a good piano for $50, delivered.," he said. He had it hoisted up the outside of the building, and was ready to go. A couple of months later, the jazz composers Dick Cary and Hall Overton each sublet a floor from Mr. Young. Mr. Cary took a grand piano to his space, and Mr. Overton took two uprights. There were now four good pianos in the building.

Mr. Overton and Mr. Monk, both chain smokers, met frequently in the loft to prepare for elaborate concerts at Town Hall in 1959, Lincoln Center in 1963 and Carnegie Hall in 1964. "Theyd have the whole place filled with smoke," Mr. Young said in Double take. "They would sit at the two pianos for hours, working on their charts, smoking the whole time."

Davis, Mingus and Mr. Charles used the loft to home the sound heard on the record "Blue Moods." Regular jam sessions were on Monday nights. Mingus was in the loft on the night in 1955 when the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter called to tell him that Charlie Parker had just died in her living room.

In 1957, Mr. Overton rented some of his space to the photographer W. Eugene Smith, who shot 20,000 pictures of the sessions there. He and Mr. Young had planned to write a book on the loft scene, but Smith died in 1978.

Mr. Young, who also made several documentaries and science-fiction film, was finally evicted from his illegal space in 1964. He moved to a loft on Canal Street, where he survived by painting watercolors and occasional albums covers. He had been thinking recently about moving to Europe. "He got what he needed from New York," Ms. Young said.

We also append a portrait of David X Young, as he called himself, by W Eugene Smith, in the loft they shared.

Contact us to arrange special shipping, local delivery, or pickup at the warehouse.