James Hueter

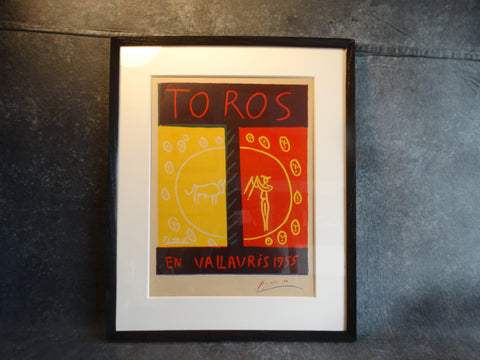

James Hueter - Portrait of a Young Man - Oil on Board P3035

Regular price

$2,700.00

An elegant work by a distinguished California modernist.

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG MAN.

Frame was Hand carved by him.

A cryptic notation on the back "Head Behind - pencil" and the artist's name joins other notes of exhibitions at both the Pasadena Art Museum and the Long Beach Art Museum as well as naming the owners from it was, on at least one occasion, on loan.

Measures 25" x 32", frame is 34" x 41"

James Hueter, 1925-2020

Mr. Hueter was drawn to Claremont, California as early as 1942.

Claremont’s supportive attitude to the arts and the proximity of his friends, fellow graduates and WWII veterans, many of whom attended the opening as active members of the local arts community, appealed to Mr. Hueter and allowed him to start a family and a career in a comfortable and inspiring environment.

The young artist’s first great influence was painter Henry McFee who introduced him to the formalist focus on structure, balance, and composition. “He had integrity; he taught me about building a painting, making a sturdy structure, in which the thoughtful, painstaking assembly of the parts becomes a beautiful unit,” Mr. Hueter explained. Other key influences included Albert Steward in sculpture, Whitney Smith in architecture, and Jean Ames in design. They inspired the artist to question his conservative views and led to his present-day experimental and open-ended direction.

In 1946, after three years in the Army, Mr. Hueter met with renowned painter Millard Sheets, who taught at Scripps College and managed the Fine Arts Program of the L.A. County Fair, and this encounter could be characterized as one of the most important and formative for the young artist. “Millard tried to build a bridge for the general public to the world of fine art,” Mr. Hueter explained. “He changed the L.A. County Fair and from 1948-1955 people saw pieces of the world’s greatest art. There is no way this could happen today.”

Another change introduced by Mr. Sheets was the establishment of an art department of the highest quality. “He hired artists who could teach, not teachers who did some art,” Mr. Hueter said. He still remembers and praises the “museum quality work” of Scripps College and the Claremont Graduate School.

These early influences laid the foundation of Mr. Hueter’s artistic views, but his work changed a lot over the years. The late 1950s and early 1960s marked the process of “breaking away” from past traditions and his focus shifted from landscape to the human figure. In the 1970s the artist decided to settle down and work on something he loved; the human face and head have remained central motifs and fields of exploration ever since.

Mr. Hueter’s first experiments with glass in the early 1970s were a result of this obsession with the human face. Initially attracted to the physical properties of glass, the artist soon discovered the conceptual elements it added to a piece. Because of the depth and the unique visual stimulation it offers, glass, both transparent and mirrored, has become a major element in Mr. Hueter’s recent work.

The use of glass and the almost obligatory presence of the human face in Mr. Hueter’s present work reveal the desire for humanity and communication, for abstraction with a solid grounded base. “You look into the painting,” the artists explained, “and the eyes look back at you. It’s a conversation.”

Mr. Hueter describes his most recent pieces as conceptually similar to his past work. “Superficially there is a change to a more dense and decorated surface after 1996,” he explained referring to the addition of texture, design, and decoration and the experimental use of mirrors, wood, and steel, “but really it is all a continuation and an elaboration of what I did before.”

Guest Curator Steve Comba said that these recent works of striking structure and substance mark the closest Mr. Hueter has ever come to the “art fashions” of the time. “James is an artists’ artist,” Mr. Comba explained. “He is well-known to a small group of devotees, but his work has not been as widely known and celebrated as one would expect.”

Mr. Comba identifies the complex nature of the artist’s work along with his focused seriousness and modesty as possible reasons for this past “invisibility.” William Moreno, Executive Director of the Claremont Museum of Art, also speculated that Mr. Hueter’s “very particular kind of work” has limited his audience in the past. “His recent work, however, will appeal to young artists,” Mr. Moreno predicted. “It explores very current ideas.”

For the artist himself, this “invisibility” has been caused by circumstances more than anything else. He explained that his family has always been a first priority. “It’s not that I didn’t want to be known,” Mr. Hueter said. “It just didn’t happen.” In the words of Mr. Comba, the main goal of the Retrospective, which will be open until May 3rd, 2009, is to “right this obvious wrong.”

Mr. Hueter does not see himself as one of the “most prominent local heroes,” but the message he directs at young artists is rich and valuable. “Look and learn without bias from everything you can,” the artist said. “To copy the surface is not enough. You have to get inside things and understand them for yourself; that can bring you to the most interesting revelations about what you are looking at use.

In 2009 a retrospective of James Hueter’s work was shown at the Claremont Museum of Art:

Source:

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-ca-hueter29-2009mar29-story.html

Mr. Hueter was drawn to Claremont, California as early as 1942.

Claremont’s supportive attitude to the arts and the proximity of his friends, fellow graduates and WWII veterans, many of whom attended the opening as active members of the local arts community, appealed to Mr. Hueter and allowed him to start a family and a career in a comfortable and inspiring environment.

The young artist’s first great influence was painter Henry McFee who introduced him to the formalist focus on structure, balance, and composition. “He had integrity; he taught me about building a painting, making a sturdy structure, in which the thoughtful, painstaking assembly of the parts becomes a beautiful unit,” Mr. Hueter explained. Other key influences included Albert Steward in sculpture, Whitney Smith in architecture, and Jean Ames in design. They inspired the artist to question his conservative views and led to his present-day experimental and open-ended direction.

In 1946, after three years in the Army, Mr. Hueter met with renowned painter Millard Sheets, who taught at Scripps College and managed the Fine Arts Program of the L.A. County Fair, and this encounter could be characterized as one of the most important and formative for the young artist. “Millard tried to build a bridge for the general public to the world of fine art,” Mr. Hueter explained. “He changed the L.A. County Fair and from 1948-1955 people saw pieces of the world’s greatest art. There is no way this could happen today.”

Another change introduced by Mr. Sheets was the establishment of an art department of the highest quality. “He hired artists who could teach, not teachers who did some art,” Mr. Hueter said. He still remembers and praises the “museum quality work” of Scripps College and the Claremont Graduate School.

These early influences laid the foundation of Mr. Hueter’s artistic views, but his work changed a lot over the years. The late 1950s and early 1960s marked the process of “breaking away” from past traditions and his focus shifted from landscape to the human figure. In the 1970s the artist decided to settle down and work on something he loved; the human face and head have remained central motifs and fields of exploration ever since.

Mr. Hueter’s first experiments with glass in the early 1970s were a result of this obsession with the human face. Initially attracted to the physical properties of glass, the artist soon discovered the conceptual elements it added to a piece. Because of the depth and the unique visual stimulation it offers, glass, both transparent and mirrored, has become a major element in Mr. Hueter’s recent work.

The use of glass and the almost obligatory presence of the human face in Mr. Hueter’s present work reveal the desire for humanity and communication, for abstraction with a solid grounded base. “You look into the painting,” the artists explained, “and the eyes look back at you. It’s a conversation.”

Mr. Hueter describes his most recent pieces as conceptually similar to his past work. “Superficially there is a change to a more dense and decorated surface after 1996,” he explained referring to the addition of texture, design, and decoration and the experimental use of mirrors, wood, and steel, “but really it is all a continuation and an elaboration of what I did before.”

Guest Curator Steve Comba said that these recent works of striking structure and substance mark the closest Mr. Hueter has ever come to the “art fashions” of the time. “James is an artists’ artist,” Mr. Comba explained. “He is well-known to a small group of devotees, but his work has not been as widely known and celebrated as one would expect.”

Mr. Comba identifies the complex nature of the artist’s work along with his focused seriousness and modesty as possible reasons for this past “invisibility.” William Moreno, Executive Director of the Claremont Museum of Art, also speculated that Mr. Hueter’s “very particular kind of work” has limited his audience in the past. “His recent work, however, will appeal to young artists,” Mr. Moreno predicted. “It explores very current ideas.”

For the artist himself, this “invisibility” has been caused by circumstances more than anything else. He explained that his family has always been a first priority. “It’s not that I didn’t want to be known,” Mr. Hueter said. “It just didn’t happen.” In the words of Mr. Comba, the main goal of the Retrospective, which will be open until May 3rd, 2009, is to “right this obvious wrong.”

Mr. Hueter does not see himself as one of the “most prominent local heroes,” but the message he directs at young artists is rich and valuable. “Look and learn without bias from everything you can,” the artist said. “To copy the surface is not enough. You have to get inside things and understand them for yourself; that can bring you to the most interesting revelations about what you are looking at use.

In 2009 a retrospective of James Hueter’s work was shown at the Claremont Museum of Art:

Source:

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-ca-hueter29-2009mar29-story.html